Early studies

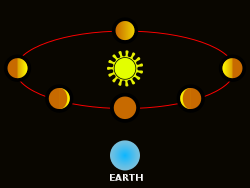

Venus was known in the Hindu Jyotisha since early times as the planet Shukra.[64][65] In the West, before the advent of the telescope, Venus was known as a 'wandering star'. Several cultures historically held its appearances as a morning and evening star to be those of two separate bodies. Pythagoras is usually credited with recognizing that the morning and evening stars were a single body in the sixth century BC, though he thought that Venus orbited the Earth.[66] When Galileo first observed the planet in the early 17th century, he found that it showed phases like the Moon, varying from crescent to gibbous to full and vice versa. When Venus is furthest from the Sun in the sky it shows a half-lit phase and when it is closest to the Sun in the sky it shows as a crescent or full phase. This could be possible only if Venus orbited the Sun, and this was among the first observations to clearly contradict the Ptolemaic geocentric model that the Solar System was concentric and centered on the Earth.[67]

The atmosphere of Venus was discovered in 1761 by Russian polymath Mikhail Lomonosov.[68][69] Venus's atmosphere was observed in 1790 by Johann Schröter. Schröter found that when the planet was a thin crescent, the cusps extended through more than 180°. He correctly surmised that this was due to scattering of sunlight in a dense atmosphere. Later, Chester Smith Lyman observed a complete ring around the dark side of the planet when it was at inferior conjunction, providing further evidence for an atmosphere.[70] The atmosphere complicated efforts to determine a rotation period for the planet, and observers such as Giovanni Cassini and Schröter incorrectly estimated periods of about 24 hours from the motions of markings on the planet's apparent surface.[71]

Ground-based research

Little more was discovered about Venus until the 20th century. Its almost featureless disc gave no hint as to what its surface might be like, and it was only with the development of spectroscopic, radar and ultraviolet observations that more of its secrets were revealed. The first UV observations were carried out in the 1920s, when Frank E. Ross found that UV photographs revealed considerable detail that was absent in visible and infrared radiation. He suggested that this was due to a very dense yellow lower atmosphere with high cirrus clouds above it.[72]

Spectroscopic observations in the 1900s gave the first clues about Venus's rotation. Vesto Slipher tried to measure the Doppler shift of light from Venus, but found that he could not detect any rotation. He surmised that the planet must have a much longer rotation period than had previously been thought.[73] Later work in the 1950s showed that the rotation was retrograde. Radar observations of Venus were first carried out in the 1960s, and provided the first measurements of the rotation period which were close to the modern value.[74]

Radar observations in the 1970s revealed details of Venus's surface for the first time. Pulses of radio waves were beamed at the planet using the 300 m radio telescope at Arecibo Observatory, and the echoes revealed two highly reflective regions, designated the Alpha and Beta regions. The observations also revealed a bright region attributed to mountains, which was called Maxwell Montes.[75] These three features are now the only ones on Venus which do not have female names.[76]

Exploration

Early efforts

The first robotic space probe mission to Venus, and the first to any planet, began on February 12, 1961 with the launch of the Venera 1 probe. The first craft of the otherwise highly successful Soviet Venera program, Venera 1 was launched on a direct impact trajectory, but contact was lost seven days into the mission, when the probe was about 2 million km from Earth. It was estimated to have passed within 100,000 km from Venus in mid-May.[77]

The United States exploration of Venus also started badly with the loss of the Mariner 1 probe on launch. The subsequent Mariner 2 mission enjoyed greater success, and after a 109-day transfer orbit on December 14, 1962 it became the world's first successful interplanetary mission, passing 34,833 km above the surface of Venus. Its microwave and infrared radiometers revealed that while Venus's cloud tops were cool, the surface was extremely hot—at least 425 °C, finally ending any hopes that the planet might harbor ground-based life. Mariner 2 also obtained improved estimates of Venus's mass and of the astronomical unit, but was unable to detect either a magnetic field or radiation belts.[78]

Atmospheric entry

The Soviet Venera 3 probe crash-landed on Venus on March 1, 1966. It was the first man-made object to enter the atmosphere and strike the surface of another planet, though its communication system failed before it was able to return any planetary data.[79] Venus's next encounter with an unmanned probe came on October 18, 1967 when Venera 4 successfully entered the atmosphere and deployed a number of science experiments. Venera 4 showed that the surface temperature was even hotter than Mariner 2 had measured at almost 500 °C, and that the atmosphere was about 90 to 95% carbon dioxide. The Venusian atmosphere was considerably denser than Venera 4's designers had anticipated, and its slower than intended parachute descent meant that its batteries ran down before the probe reached the surface. After returning descent data for 93 minutes, Venera 4's last pressure reading was 18 bar at an altitude of 24.96 km.[79]

Another probe arrived at Venus one day later on October 19, 1967 when Mariner 5 conducted a flyby at a distance of less than 4000 km above the cloud tops. Mariner 5 was originally built as backup for the Mars-bound Mariner 4, but when that mission was successful, the probe was refitted for a Venus mission. A suite of instruments more sensitive than those on Mariner 2, in particular its radio occultation experiment, returned data on the composition, pressure and density of Venus's atmosphere.[80] The joint Venera 4–Mariner 5 data were analyzed by a combined Soviet-American science team in a series of colloquia over the following year,[81] in an early example of space cooperation.[82]

Armed with the lessons and data learned from Venera 4, the Soviet Union launched the twin probes Venera 5 and Venera 6 five days apart in January 1969; they encountered Venus a day apart on May 16 and May 17 that year. The probes were strengthened to improve their crush depth to 25 bar and were equipped with smaller parachutes to achieve a faster descent. Since then-current atmospheric models of Venus suggested a surface pressure of between 75 and 100 bar, neither was expected to survive to the surface. After returning atmospheric data for a little over fifty minutes, they both were crushed at altitudes of approximately 20 km before going on to strike the surface on the night side of Venus.[79]

Surface and atmospheric science

Venera 7 represented a concerted effort to return data from the planet's surface, and was constructed with a reinforced descent module capable of withstanding a pressure of 180 bar. The module was pre-cooled prior to entry and equipped with a specially reefed parachute for a rapid 35-minute descent. Entering the atmosphere on December 15, 1970, the parachute is believed to have partially torn during the descent, and the probe struck the surface with a hard, yet not fatal, impact. Probably tilted onto its side, it returned a weak signal supplying temperature data for 23 minutes, the first telemetry received from the surface of another planet.[79]

The Venera program continued with Venera 8 sending data from the surface for 50 minutes, and Venera 9 and Venera 10 sending the first images of the Venusian landscape. The two landing sites presented very different visages in the immediate vicinities of the landers: Venera 9 had landed on a 20 degree slope scattered with boulders around 30–40 cm across; Venera 10 showed basalt-like rock slabs interspersed with weathered material.[83]

In the meantime, the United States had sent the Mariner 10 probe on a gravitational slingshot trajectory past Venus on its way to Mercury. On February 5, 1974, Mariner 10 passed within 5790 km of Venus, returning over 4000 photographs as it did so. The images, the best then achieved, showed the planet to be almost featureless in visible light, but ultraviolet light revealed details in the clouds that had never been seen in Earth-bound observations.[84]

The American Pioneer Venus project consisted of two separate missions.[85] The Pioneer Venus Orbiter was inserted into an elliptical orbit around Venus on December 4, 1978, and remained there for over thirteen years studying the atmosphere and mapping the surface with radar. The Pioneer Venus Multiprobe released a total of four probes which entered the atmosphere on December 9, 1978, returning data on its composition, winds and heat fluxes.[86]

Four more Venera lander missions took place over the next four years, with Venera 11 and Venera 12 detecting Venusian electrical storms;[87] and Venera 13 and Venera 14, landing four days apart on March 1 and March 5, 1982, returning the first color photographs of the surface. All four missions deployed parachutes for braking in the upper atmosphere, but released them at altitudes of 50 km, the dense lower atmosphere providing enough friction to allow for an unaided soft landing. Both Venera 13 and 14 analyzed soil samples with an on-board X-ray fluorescence spectrometer, and attempted to measure the compressibility of the soil with an impact probe.[87] Venera 14, though, had the misfortune to strike its own ejected camera lens cap and its probe failed to make contact with the soil.[87] The Venera program came to a close in October 1983 when Venera 15 and Venera 16 were placed in orbit to conduct mapping of the Venusian terrain with synthetic aperture radar.[88]

In 1985 the Soviet Union took advantage of the opportunity to combine missions to Venus and Comet Halley, which passed through the inner Solar System that year. En route to Halley, on June 11 and June 15, 1985 the two spacecraft of the Vega program each dropped a Venera-style probe (of which Vega 1's partially failed) and released a balloon-supported aerobot into the upper atmosphere. The balloons achieved an equilibrium altitude of around 53 km, where pressure and temperature are comparable to those at Earth's surface. They remained operational for around 46 hours, and discovered that the Venusian atmosphere was more turbulent than previously believed, and subject to high winds and powerful convection cells.[89][90]

Radar mapping

The United States' Magellan probe was launched on May 4, 1989 with a mission to map the surface of Venus with radar.[21] The high-resolution images it obtained during its 4½ years of operation far surpassed all prior maps and were comparable to visible-light photographs of other planets. Magellan imaged over 98% of Venus's surface by radar[91] and mapped 95% of its gravity field. In 1994, at the end of its mission, Magellan was deliberately sent to its destruction into the atmosphere of Venus in an effort to quantify its density.[92] Venus was observed by the Galileo and Cassini spacecraft during flybys on their respective missions to the outer planets, but Magellan would otherwise be the last dedicated mission to Venus for over a decade.[93][94]

Current and future missions

The Venus Express probe was designed and built by the European Space Agency. Launched on November 9, 2005 by a Russian Soyuz-Fregat rocket procured through Starsem, it successfully assumed a polar orbit around Venus on April 11, 2006.[95] The probe is undertaking a detailed study of the Venusian atmosphere and clouds, and will also map the planet's plasma environment and surface characteristics, particularly temperatures. Its mission is intended to last a nominal 500 Earth days, or around two Venusian years.[95] One of the first results emerging from Venus Express is the discovery that a huge double atmospheric vortex exists at the south pole of the planet.[95]

NASA's MESSENGER mission to Mercury performed two flybys of Venus in October 2006 and June 2007, in order to slow its trajectory for an eventual orbital insertion of Mercury in 2011. MESSENGER collected scientific data on both those flybys.[96] The European Space Agency (ESA) will also launch a mission to Mercury, called BepiColombo, which will perform two flybys of Venus in August 2013 before it reaches Mercury orbit in 2019.[97]

Future missions to Venus are planned. Japan's aerospace body JAXA is planning to launch its Venus climate orbiter, PLANET-C, in 2010.[98] Under its New Frontiers Program, NASA has proposed a lander mission called the Venus In-Situ Explorer to land on Venus to study surface conditions and investigate the elemental and mineralogical features of the regolith. The probe would be equipped with a core sampler to drill into the surface and study pristine rock samples not weathered by the very harsh surface conditions. The Venera-D (Russian: Венера-Д) probe is a proposed Russian space probe to Venus, to be launched around 2016 with its goal to make remote-sensing observations around the planet Venus and deploying a lander, based on the Venera design, capable of surviving for a long duration on the planet's surface. Other proposed Venus exploration concepts include rovers, balloons, and airplanes.[99]

Manned Venus flyby

A manned Venus flyby mission, using Apollo program hardware, was proposed in the late 1960s.[100] The mission was planned to launch in late October or early November 1973, and would have used a Saturn V to send three men to fly past Venus in a flight lasting approximately one year. The spacecraft would have passed approximately 5,000 kilometres from the surface of Venus about four months later.[100]

In culture

The adjective Venusian is commonly used for items related to Venus, though the Latin adjective is the rarely used Venerean; the archaic Cytherean is still occasionally encountered. Venus is the only planet in the Solar System named after a female figure,[a] although three dwarf planets – Ceres, Eris and Haumea – along with hundreds of the first discovered asteroids also have feminine names.[citation needed]

Historic understanding

As one of the brightest objects in the sky, Venus has been known since prehistoric times and as such has gained an entrenched position in human culture. It is described in Babylonian cuneiformic texts such as the Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa, which relates observations that possibly date from 1600 BC.[101] The Babylonians named the planet Ishtar (Sumerian Inanna), the personification of womanhood, and goddess of love.[102]

The Ancient Egyptians believed Venus to be two separate bodies and knew the morning star as Tioumoutiri and the evening star as Ouaiti.[103] Likewise, believing Venus to be two bodies, the Ancient Greeks called the morning star Φωσφόρος, Phosphoros (Latinized Phosphorus), the "Bringer of Light" or Ἐωσφόρος, Eosphoros (Latinized Eosphorus), the "Bringer of Dawn". The evening star they called Hesperos (Latinized Hesperus) (Ἓσπερος, the "star of the evening"). By Hellenistic times, the ancient Greeks realized the two were the same planet.[104] Hesperos would be translated into Latin as Vesper and Phosphoros as Lucifer ("Light Bearer"), a poetic term later used to refer to the fallen angel cast out of heaven.[b] The Romans would later name the planet in honor of their goddess of love, Venus,[105][dubious ] whereas the Greeks used the name of her Greek counterpart, Aphrodite (Phoenician Astarte).[106] Pliny the Elder (Natural History, ii,37) identified the planet Venus with Isis.[107]

Venus was important to the Maya civilization, who developed a religious calendar based in part upon its motions, and held the motions of Venus to determine the propitious time for events such as war. They named it Noh Ek', the Great Star, and Xux Ek', the Wasp Star. The Maya were aware of the planet's synodic period, and could compute it to within a hundredth part of a day.[108] The Maasai people named the planet Kileken, and have an oral tradition about it called The Orphan Boy.[109]

Venus is important in many Australian aboriginal cultures, such as that of the Yolngu people in Northern Australia. The Yolngu gather after sunset to await the rising of Venus, which they call Barnumbirr. As she approaches, in the early hours before dawn, she draws behind her a rope of light attached to the Earth, and along this rope, with the aid of a richly decorated "Morning Star Pole", the people are able to communicate with their dead loved ones, showing that they still love and remember them. Barnumbirr is also an important creator-spirit in the Dreaming, and "sang" much of the country into life.[110]

In western astrology, derived from its historical connotation with goddesses of femininity and love, Venus is held to influence desire and sexual fertility.[111] In Indian Vedic astrology, Venus is known as Shukra,[65] meaning "clear, pure" or "brightness, clearness" in Sanskrit. One of the nine Navagraha, it is held to affect wealth, pleasure and reproduction; it was the son of Bhrgu, preceptor of the Daityas, and guru of the Asuras.[64][112] Modern Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese cultures refer to the planet literally as the gold star (Chinese: 金星), based on the Five elements.[citation needed] The ancient Chinese called the star Tai Bai (太白) if sighted in the evening, and Qi Ming (启明) in the morning, and it is both a representation of an important Taoist deity and a symbol of war.[citation needed] Lakotan spirituality refers to Venus as the daybreak star, and associates it with the last stage of life and wisdom.[citation needed]

In the metaphysical system of Theosophy, it is believed that on the etheric plane of Venus there is a civilization hundreds of millions of years in advance of Earth’s[113] and it is also believed that the governing deity of Earth, Sanat Kumara, is from Venus. [114]

The astronomical symbol for Venus is the same as that used in biology for the female sex: a circle with a small cross beneath.[115] The Venus symbol also represents femininity, and in Western alchemy stood for the metal copper.[115] Polished copper has been used for mirrors from antiquity, and the symbol for Venus has sometimes been understood to stand for the mirror of the goddess.[115]

Perhaps the strangest appearance of Venus in literature is as the harbinger of destruction in Immanuel Velikovsky's Worlds in Collision (1950). In this intensely controversial book, Velikovsky argued that many seemingly unbelievable stories in the Old Testament are actually true recollections of times when Venus nearly collided with the Earth – when it was still a comet and had not yet become the docile planet that we know today. He contended that Venus caused most of strange events of the Exodus. He cites legends in many other cultures (such as Greek, Mexican, Chinese and Indian) indicating that the effects of the near-collision were global. The scientific community rejected his wildly unorthodox book, however it became a bestseller.[116]

In science fiction

Venus's impenetrable cloud cover gave science fiction writers free rein to speculate on conditions at its surface; all the more so when early observations showed that not only was it very similar in size to Earth, it possessed a substantial atmosphere. Closer to the Sun than Earth, the planet was frequently depicted as warmer, but still habitable by humans.[117] The genre reached its peak between the 1930s and 1950s, at a time when science had revealed some aspects of Venus, but not yet the harsh reality of its surface conditions. Findings from the first missions to Venus showed the reality to be very different, and brought this particular genre to an end.[118] As scientific knowledge of Venus advanced, so science fiction authors endeavored to keep pace, particularly by conjecturing human attempts to terraform Venus.[119]

No comments:

Post a Comment